When you sign a contract-whether it’s for software, equipment, consulting, or even a simple service-you’re not just agreeing to pay for something. You’re also agreeing to take on risk. And that’s where liability and indemnification come in. These aren’t just legal buzzwords. They’re the real-world safety nets that decide who pays when things go wrong. If you’ve ever wondered why contracts are so long, or why lawyers spend hours arguing over one paragraph, this is why.

What Liability Actually Means in a Transaction

Liability is simple: it’s legal responsibility. If your company causes harm-say, a faulty product injures someone, or your software crashes and loses a client’s data-you’re on the hook. Liability isn’t about intent. It’s about outcome. And in most business deals, someone has to carry that burden. In generic transactions, liability doesn’t just come from laws. It comes from contracts. You might think, “I didn’t break anything, so why am I responsible?” But contracts change the rules. A vendor might agree to be liable for any data breach caused by their system. A buyer might agree to cover taxes from pre-closing periods. These aren’t accidents. They’re negotiated assignments of risk. The key point? Liability can be shifted. But only if it’s written down clearly. Without a contract saying otherwise, you’re stuck with whatever the law says-and that’s often broad, unpredictable, and expensive.Indemnification: The Contractual Insurance Policy

Indemnification is how one party promises to cover the other’s losses. Think of it like insurance built into the deal. If Party A breaks a promise, Party B gets paid back for the damage. That includes legal fees, settlement costs, fines, even lost profits. It’s not magic. It’s a promise, written in plain English (or legalese). But it’s powerful. For example:- A software company agrees to indemnify its customer if their code infringes someone’s patent.

- A seller promises to cover any tax penalties from before the sale date.

- A contractor agrees to pay for injuries to their own workers on your site.

The Seven Parts of a Solid Indemnification Clause

Not all indemnification clauses are created equal. A weak one leaves you exposed. A strong one protects you. Here’s what every good clause needs:- Scope of Indemnification - What exactly is covered? Legal fees? Third-party lawsuits? Regulatory fines? The clause must list specific types of losses. Vague language like “any damages” is dangerous.

- Triggering Events - What starts the obligation? Breach of contract? Negligence? Failure to comply with laws? Be specific. “Any claim” is too broad. “Claims arising from failure to maintain cybersecurity standards” is better.

- Duration - How long does this protection last? Some clauses expire when the contract ends. Others last for years. Tax liabilities, for example, often survive 3-7 years. IP infringement? Could be forever.

- Limitations and Exclusions - Not all losses are covered. Most contracts exclude indirect damages (like lost profits) or punitive damages. Caps on total payouts are common too-say, no more than the total contract value.

- Claim Procedures - You can’t just send a bill. You have to notify the other party within a set time, usually 30-60 days. Failure to notify? You might lose your right to claim.

- Insurance Requirements - Does the indemnifying party have to carry insurance? If so, what kind? General liability? Cyber? Professional errors? And what’s the minimum coverage? $1M? $5M?

- Governing Law and Jurisdiction - If a dispute arises, where does it get settled? Which state’s laws apply? This matters because rules vary. California treats indemnity differently than Texas.

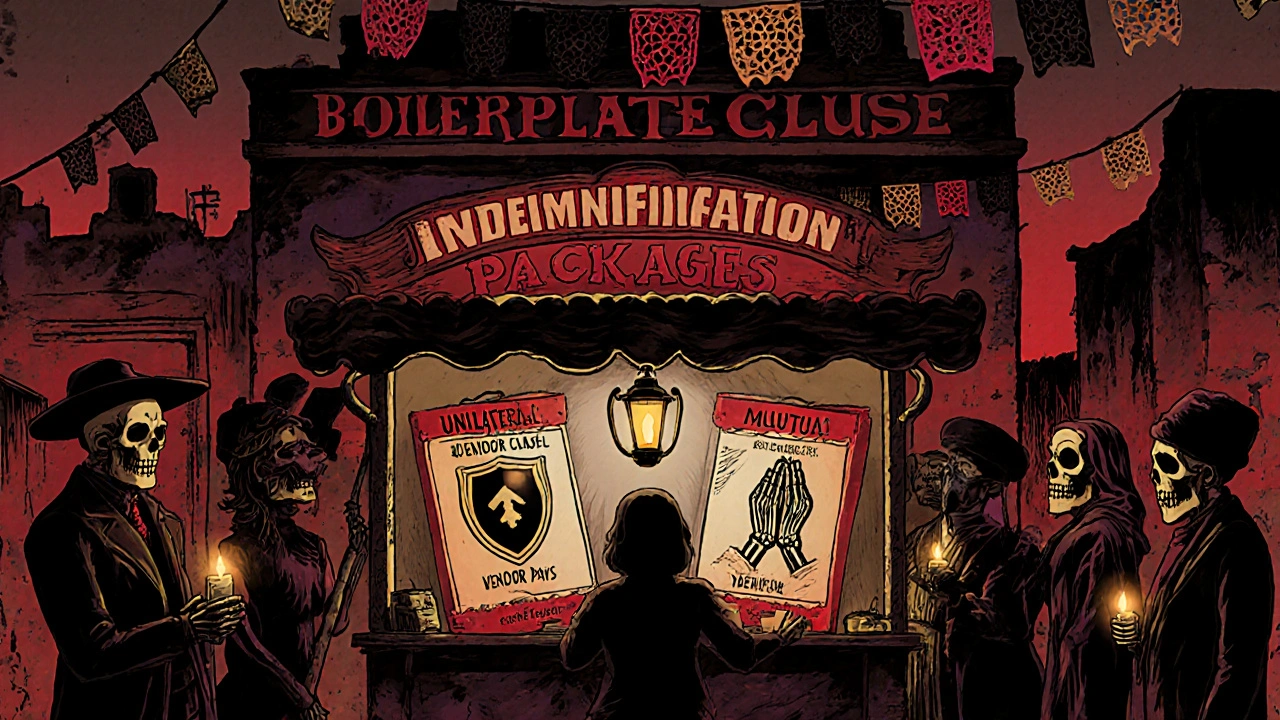

Mutual vs. One-Sided Indemnification

There are two main types of indemnification: mutual and unilateral.- Unilateral - Only one party pays. This is the norm in vendor-customer deals. A software vendor indemnifies the buyer for IP infringement. The buyer doesn’t owe anything back. It’s about power. The buyer has leverage; the vendor has to agree or lose the deal.

- Mutual - Both parties cover each other. Common in construction, joint ventures, or M&A deals. If your team causes an injury on-site, you pay. If mine does, I pay. Fair? Maybe. But it requires trust and balance.

Indemnify, Defend, Hold Harmless - What’s the Difference?

These three terms are often lumped together. But legally, they’re different.- Indemnify - Pay for the loss. You cover the cost after the fact.

- Defend - Pay for the legal battle. This includes attorney fees, court costs, expert witnesses. It’s proactive.

- Hold Harmless - You can’t sue me back. Even if I’m partly at fault, you promise not to hold me liable.

What Gets Indemnified? Fundamental vs. Non-Fundamental

In mergers and acquisitions, indemnification ties directly to representations and warranties. These are promises about the business:- Fundamental reps - Core truths: “We own this company,” “We have the legal right to sell it,” “No hidden debts,” “Taxes are paid.” These usually survive 3-7 years.

- Non-fundamental reps - Operational stuff: “Our employees are properly classified,” “Our IP is clean,” “No pending lawsuits.” These often last only 12-18 months.

Practical Traps to Avoid

Even experienced professionals get tripped up. Here are the most common mistakes:- Not setting a cap - Without a limit, you could be on the hook for millions, even if the contract was worth $50,000.

- Ignoring notification deadlines - Miss the 30-day window? You lose your claim, no matter how valid it is.

- Forgetting insurance - What if the indemnifying party goes bankrupt? A clause saying “we’ll pay” means nothing if they have no money.

- Using boilerplate language - Copy-pasting from another contract? That’s how you end up with conflicting terms or irrelevant obligations.

- Not understanding control rights - Who runs the legal defense? If you’re the indemnified party, you want control. If you’re the indemnifier, you want to manage the defense to keep costs down. This is often a major negotiation point.

Real-World Example: A Data Breach

Let’s say you’re a small clinic that hires a vendor to manage patient records. The vendor’s system gets hacked. Patient data is stolen. You get sued. You get fined by HIPAA. You pay for credit monitoring for 5,000 patients. If your contract says the vendor will indemnify you for data breaches caused by their negligence, they owe you everything: legal fees, fines, notification costs, and more. But if the clause says “indemnify for third-party claims only,” you’re out of luck. HIPAA fines aren’t third-party claims-they’re government penalties. If the clause doesn’t say “regulatory fines,” you can’t claim them. That’s why wording matters. One word changes who pays.Bottom Line: Know What You’re Signing

Liability and indemnification aren’t optional. They’re unavoidable. The only question is: who bears the risk? If you’re buying something, push for broad indemnification. Make sure it covers legal fees, regulatory fines, and third-party claims. Set a reasonable cap. Require insurance. Know the timeline. If you’re selling something, limit your exposure. Narrow the scope. Exclude indirect damages. Set a cap. Shorten the survival period. Require notice within 30 days. Push back on “hold harmless” unless you’re confident you won’t be blamed for things you didn’t do. Don’t assume your lawyer will fix it. Read the clause. Ask: “What happens if this goes wrong?” If you can’t answer that, don’t sign. These clauses don’t exist to be pretty. They exist to protect someone. Make sure it’s you.Is indemnification the same as insurance?

No. Insurance is a policy from a third-party company that pays out when a covered event happens. Indemnification is a promise between two parties in a contract. One party agrees to pay the other for losses. Insurance can back up indemnification, but it’s not the same thing. A contract saying “we’ll indemnify you” means nothing if the party has no money. That’s why insurance requirements are often part of the clause.

Can I waive indemnification entirely?

Technically, yes. But it’s rare. Most parties expect some level of protection. If you refuse to indemnify at all, you’ll likely lose the deal. Buyers won’t risk taking on unknown liabilities. Sellers in M&A deals almost always provide some indemnification. The goal isn’t to eliminate it-it’s to limit it to what’s fair and reasonable.

What if the indemnifying party goes bankrupt?

Then you’re stuck. A promise to pay is worthless if the person can’t pay. That’s why indemnification clauses often require the indemnifying party to maintain insurance. If they go under, you can still file a claim with their insurer. Without insurance, you’re just another creditor in bankruptcy court-and you’ll likely get pennies on the dollar.

Do I need a lawyer to draft an indemnification clause?

Yes. Indemnification clauses are among the most heavily negotiated parts of any contract. A poorly written clause can cost you millions. Even small wording changes-like adding “direct damages only” or shortening the survival period-can make a huge difference. Don’t rely on templates. Get legal help tailored to your deal.

How long should indemnification last?

It depends on the risk. For tax issues or ownership claims, 3-7 years is standard. For product defects or IP infringement, it could be longer. For routine operational warranties, 12-18 months is typical. The key is matching the duration to the nature of the risk. Don’t let it drag on forever unless you’re forced to.

14 Comments

Alyssa Fisher November 8, 2025

It's wild how much power lies in a single clause. I used to think contracts were just formalities-until I saw a startup get crushed because they didn't cap indemnification. One line, millions gone. It’s not about being paranoid. It’s about being literate in the language of risk.

People treat legal docs like they’re poetry. They’re not. They’re blueprints for disaster-or protection. And if you don’t read them like a detective, you’re handing someone else the keys to your business.

Indemnification isn’t insurance. It’s a promise. And promises without teeth are just noise.

Jay Wallace November 8, 2025

Ugh. Another ‘read the fine print’ lecture. Like anyone in a small biz has time to parse legalese. You think the vendor’s gonna let you change their boilerplate? Nah. They’ll just walk. And then you’re stuck with some no-name freelancer who doesn’t even have liability insurance. So yeah-go ahead and ‘know what you’re signing.’ Meanwhile, I’m just trying to get my damn software deployed.

Stop pretending this is fair. It’s not. It’s power. And if you’re not the one with the money, you lose. Again.

Alyssa Salazar November 9, 2025

Okay but let’s talk about the DEFEND vs INDEMNIFY vs HOLD HARMLESS triad-this is where people get *so* tripped up. Defend means they have to hire counsel and run the litigation. Indemnify means they pay the judgment. Hold harmless? That’s the nuclear option-it bars you from suing them even if they’re 70% at fault. Most people don’t realize hold harmless can be unenforceable in some states if it’s overbroad. California’s Civil Code § 2782 makes this a minefield.

And don’t even get me started on how ‘third-party claims’ excludes regulatory fines. That’s a trapdoor for every healthcare and fintech startup. HIPAA penalties? Gone. GDPR? Not covered. You need explicit language. Period.

Beth Banham November 11, 2025

I read this and just felt… calmer. Like someone finally explained why contracts feel so scary without making me feel dumb for not understanding them.

I’m not a lawyer. I run a tiny design studio. But now I know to ask: ‘What happens if this breaks?’ And if they can’t answer? I walk. Not because I’m paranoid. Because I’m smart.

Thanks for writing this. I’m saving it.

Brierly Davis November 12, 2025

YES. This. So many people think legal stuff is for ‘other people.’ Nope. It’s for YOU.

Just last week, a client asked me to sign a contract with zero indemnity. I said no. They were shocked. I said: ‘If my code crashes and your site goes down, you’re gonna want someone to pay for it. That’s not me being difficult-that’s me being responsible.’

Don’t be afraid to push back. You’re not being difficult. You’re being professional. 😊

Amber O'Sullivan November 12, 2025

Indemnification is just a fancy word for ‘I’ll pay if you get sued’ and if you don’t spell it out you’re asking for trouble

Everyone thinks they’re protected until they’re not and then they cry about it in court

Just say what you mean and move on

Jim Oliver November 14, 2025

Of course you need a lawyer. You also need to stop pretending you’re not being exploited.

98% of small businesses sign these contracts without negotiation. They think ‘it’s standard.’ It’s not standard-it’s predatory.

And yes, ‘hold harmless’ is redundant. But lawyers use it because they want to bill you for 3 more hours explaining why it’s ‘best practice.’

Wake up. You’re not a client. You’re a revenue stream.

William Priest November 15, 2025

Bro. Indemnification clauses are the reason I majored in law. This post? Cute. But you missed the nuance. The real issue isn’t the clause-it’s the enforceability under the ‘conscionability’ doctrine. Courts in NY and CA routinely strike down indemnity clauses that are one-sided and unconscionable, especially in B2C or small biz contexts.

And ‘mutual indemnity’? That’s a myth unless both parties have equal leverage. Which they never do. The buyer always has the upper hand. Always.

Also, ‘software’ doesn’t ‘crash.’ It fails due to unpatched vulnerabilities. Get your terminology right.

Ryan Masuga November 16, 2025

Man I wish I’d read this 5 years ago. I signed a contract once that had a 10-year indemnity for IP claims. We were a $200k startup. The vendor? Fortune 500. They got sued for patent infringement. Guess who got hit with a $2.3M claim?

Turns out the clause didn’t cap it. Didn’t require insurance. Didn’t even say ‘direct damages only.’

Lesson learned: If it’s not in writing, it’s not real. And if it’s not limited, it’s a liability time bomb.

Thanks for the clarity. Sharing this with my whole team.

Jennifer Bedrosian November 17, 2025

Okay so I just got served with a subpoena and I’m crying in my car because I signed a contract without reading it and now I owe $180k for a data breach I didn’t cause and the vendor says ‘it’s not our fault’ and I’m like WHAT DID I AGREE TO

THIS ARTICLE IS A LIFE SAVIOR

IF YOU’RE READING THIS AND YOU’RE ABOUT TO SIGN A CONTRACT-STOP. BREATHE. ASK FOR THE INDEMNITY CLAUSE. READ IT. THEN SIGN. OR DON’T. BUT DON’T JUST CLICK ‘I AGREE’

I’M SO SORRY TO EVERYONE WHO’S BEEN THERE

Lashonda Rene November 18, 2025

So like I was reading this and I realized I’ve been signing these things for years and never really understood what indemnify even meant. I thought it was like insurance but now I get it’s more like a promise between two people and if they don’t have money then it’s useless. I used to think lawyers were just being dramatic but now I see they’re trying to protect you. I’m gonna start asking questions before I sign anything. Like what if this breaks? Who pays? How long does it last? And do they have insurance? I used to think that was rude but now I think it’s just being smart. Also I never knew about the 30 day notice thing and I almost missed it once. So yeah. This helped. A lot.

Andy Slack November 20, 2025

Just got done negotiating a SaaS contract. Took 3 weeks. 17 revisions. We cut the indemnity period from 7 years to 2. Added a $500k cap. Required cyber insurance with $2M minimum. Removed ‘hold harmless’ entirely.

Client was furious. Said we were ‘unreasonable.’

We walked. They came back 2 days later with our terms.

Don’t be afraid to say no. You’re not being difficult. You’re being smart.

Rashmi Mohapatra November 21, 2025

you think this is bad? wait till you work with indian vendors. they write contracts in broken english and then say 'we indemnify for all damages' but when you get sued they say 'we never agreed to that' and disappear. also they never have insurance. so you pay. again. and again. and again. this is why i only work with american companies now. sorry not sorry.

Abigail Chrisma November 22, 2025

Thank you for writing this with such clarity. I’m from a country where contracts are often verbal or written in vague terms. Seeing this breakdown made me realize how much protection we’re missing out on.

I’m sharing this with my team in Nairobi and Lagos. We’ve been signing things blindly because we thought ‘it’s just a formality.’ Now we know better.

This isn’t just legal advice. It’s economic justice.

Keep writing like this.