When you’re flying across time zones with diabetes, your body doesn’t care about your flight schedule. It still needs insulin at the right times - and if you don’t adjust, your blood sugar can go dangerously high or crash hard. This isn’t just a minor inconvenience. It’s a real risk that can land you in the hospital mid-flight or leave you stranded in a foreign country with no access to help. The good news? With the right plan, you can travel safely without constant fear of low or high blood sugar.

Why Time Zones Mess With Your Insulin

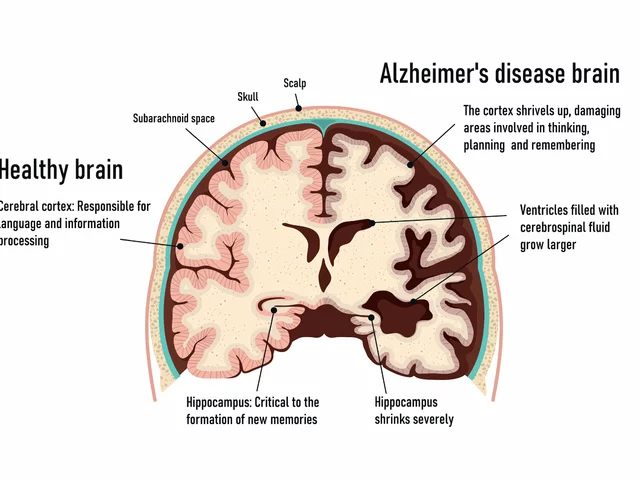

Your insulin schedule is built around your daily rhythm: breakfast, lunch, dinner, bedtime. When you fly from New York to Tokyo, you lose 13 hours. That means your body thinks it’s time for dinner at 3 a.m. local time - but your pancreas (or your insulin pump) hasn’t caught up. The same thing happens going west. Flying from Los Angeles to London adds 8 hours. Now you’re eating breakfast at 11 p.m. your body’s clock says it’s still night. This mismatch throws off your insulin timing. If you take your usual dose at the same clock time, you might overdose on insulin during a short day (eastbound) or underdose during a long day (westbound). The result? Hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, or worse - the Somogyi rebound, where your body overcorrects after a low and spikes your sugar dangerously high. Studies show about 12% of travelers who don’t adjust properly experience this rebound effect.Eastbound Travel: Shorter Days, Less Insulin

Flying east - say, from Chicago to Paris - means your day gets shorter. You lose hours. Your body doesn’t need as much insulin because you’re not active or eating for as long. The rule of thumb: reduce your basal (long-acting) insulin by 20-33% on the travel day. For example, if you normally take 20 units of Lantus at bedtime, take only 14-16 units the night you fly east. Skip your usual evening snack. Don’t try to eat on your old schedule. Eat when it’s actually daytime at your destination, even if your body says it’s midnight. Rapid-acting insulin (like Humalog or NovoLog) for meals should be adjusted based on local meal times. If you land at 8 a.m. local time but your body thinks it’s 3 a.m., don’t take your full breakfast dose right away. Wait until you’re actually awake and ready to eat. Take half your usual dose if you’re unsure. Better to be slightly high than dangerously low.Westbound Travel: Longer Days, More Insulin

Going west - like from Seattle to Rome - stretches your day. Now you’ve got extra hours where your body is still burning glucose but your insulin has worn off. This is where people get caught off guard. They think, “I already ate, I don’t need more insulin,” and end up with sky-high blood sugar by the next morning. The fix? Add an extra dose of rapid-acting insulin. Take about half to three-quarters of your usual meal dose 4-6 hours after your last meal. For example, if you ate dinner at 7 p.m. local time and your usual dinner dose is 8 units, take 4-6 units at 11 p.m. or midnight. This covers the extended period before your next meal. If you use basal insulin, don’t skip your usual dose. You might even need to take a slightly higher dose than normal - but only if your blood sugar is rising. Test often. Don’t guess.

Pump Users: Don’t Just Flip the Clock

If you use an insulin pump, changing the time on your device isn’t enough. Many people think, “I’ll just set it to local time when I land,” and that’s a mistake. For time zone changes over 2 hours, adjust slowly. UCLA Health recommends changing your pump time by 2 hours per day until you’re synced with local time. Jumping straight to the new time can cause dangerous highs or lows. For example, if you’re flying from New York to Los Angeles (3-hour difference), change your pump time by 1 hour on day one, another hour on day two, and the final hour on day three. This gives your body time to adapt. Newer pumps like the t:slim X2 with Control-IQ can detect time zone changes automatically using GPS. These devices adjust basal rates without you lifting a finger. If you have one, make sure it’s updated and synced before you fly.What About Insulin Pens and Injections?

If you use pens or syringes, you’re in charge of every dose. That means you need a clear plan. Write it down. Don’t rely on memory. Here’s a simple method for a basal-bolus regimen:- On the day you fly east: Take your usual morning dose at home time. Skip your usual evening dose. Wait until local morning to take your next dose - and cut it by 25%.

- On the day you fly west: Take your usual morning dose. At local dinner time, take your full evening dose. Then, 4-6 hours later, take an extra 50% of your usual dinner dose.

Travel Tips That Save Lives

You don’t need to be perfect. You need to be safe. Carry extra insulin. At least 20-30% more than you think you’ll need. Insulin can get too hot, too cold, or get lost. Don’t risk running out. Keep insulin cool. Insulin loses potency if it’s above 86°F (30°C) for more than 24 hours. Use a cooling wallet or insulated bag with a cold pack. Never check it in luggage. Test more often. Check your blood sugar every 2-4 hours during travel. Set alarms if you need to. Use a CGM if you have one - it’s the single biggest safety upgrade for travelers. Set a safety buffer. Dr. Howard Wolpert from Joslin Diabetes Center recommends keeping your blood sugar between 140-180 mg/dL on travel days. A little higher than normal gives you room to breathe if you miss a meal or get delayed. Know airline rules. TSA in the U.S. lets you carry unlimited insulin and supplies in your carry-on. Bring a letter from your doctor - it cuts security delays by 89%, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Real Stories, Real Risks

One traveler on Reddit, u/Type1Traveler, skipped a meal while flying east from Tokyo to Chicago because he thought he “didn’t need it.” His blood sugar dropped to 42 mg/dL mid-flight. He needed glucagon. He was lucky he had it. Another, GlobeTrottingGina on Diabetes Daily, flew from London to Los Angeles. She took half her usual NPH dose at her old lunch time, then 10 units of regular insulin 5 hours later - right when she landed. She stayed in range the whole trip. The difference? Planning. She knew what to do. He didn’t.When to See Your Doctor

Don’t wing it. Talk to your diabetes care team at least 4 weeks before you leave. They can help you build a custom plan based on your insulin type, activity level, and travel route. People who consult their care team before traveling have 53% fewer diabetes-related problems on the road, according to the Scottish NHS. If you’re on multiple daily injections or an insulin pump, your provider might suggest switching to a simpler regimen for the trip - like using only basal insulin and a fixed dose of rapid-acting insulin for meals. Less complexity means fewer mistakes.The Future Is Here

Technology is making this easier. New smart pens from Ypsomed (coming in 2025) will calculate dose adjustments based on your flight path. Airlines are working with the American Diabetes Association to train crew on diabetes emergencies by 2026. But for now, the best tool you have is knowledge. Know your insulin. Know your body. Know your plan. You don’t need to stop traveling because you have diabetes. You just need to be ready.Do I need to adjust insulin for a 2-hour time change?

For most people, no. If you’re crossing only 1-2 time zones, you can usually stick to your normal schedule. But if you have tight blood sugar targets or use an insulin pump, even a 2-hour shift can cause minor highs or lows. Test your glucose more often and adjust meals if needed. Some experts, like Diabetes UK, recommend small adjustments for people with very sensitive glucose control.

Can I skip insulin if I’m not eating on the plane?

Never skip your basal insulin - even if you don’t eat. Basal insulin keeps your blood sugar stable between meals and overnight. Skipping it can lead to dangerous high blood sugar. For rapid-acting insulin, yes, you can skip or reduce it if you’re not eating. But always check your blood sugar first. If it’s rising, you might still need a small dose. Never assume you’re safe just because you skipped a meal.

What if my insulin gets too hot during travel?

Insulin exposed to temperatures above 86°F (30°C) for more than 24 hours loses about 15% of its potency per day. That means your dose might not work as well. Always carry insulin in your carry-on, not checked luggage. Use a cooling wallet or insulated pouch with a cold pack. If you suspect your insulin has been overheated, replace it as soon as possible. Don’t risk using damaged insulin.

Should I use a CGM when traveling across time zones?

Yes - especially if you’re crossing three or more time zones. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) give you real-time trends, so you can see if your sugar is dropping overnight or rising after a meal. Studies show CGMs reduce severe hypoglycemia during travel by 58%. If you don’t have one, consider renting one for your trip. The safety benefit is huge.

How do I handle jet lag with insulin?

Jet lag affects your appetite and activity levels - which directly impacts insulin needs. Don’t try to force your old routine. Eat when it’s daytime at your destination, even if you’re tired. Take insulin based on local time and real meals, not your body’s clock. Dr. David Edelman from Duke University says the goal isn’t perfect timing - it’s consistency. Stick to regular meal times in the new time zone, and your body will adjust faster.

14 Comments

Lexi Brinkley November 6, 2025

I just flew from NY to Tokyo and survived 😎 I took half my Lantus and skipped my snack. My CGM screamed at me for 12 hours but I didn’t crash. Trust the plan, not your tired brain. 🍣✈️

Kelsey Veg November 6, 2025

so like... uhh basel insuline? i thought u just set ur pump and forget? i did that once and woke up at 3am with a sugar of 420. oops. 🤦♀️

Lashonda Rene November 7, 2025

i used to think time zones were just a hassle until i had a low on a flight and had to beg a flight attendant for juice. now i write down my plan like a bible. i even color code my insulin pens. green for eastbound, red for westbound, blue for ‘i forgot my plan and need help’. it’s not fancy but it keeps me alive. also always carry extra glucagon. like, two packs. just in case.

Andy Slack November 8, 2025

You’ve got this. Traveling with diabetes isn’t about being perfect. It’s about being prepared. I’ve flown 14 countries in 9 months with my pump. No crashes. No ER visits. Just planning, testing, and trusting yourself. You’re stronger than you think.

Rashmi Mohapatra November 8, 2025

why u even fly if u need so much plan? in india we just eat when hungry, take insulin when hungry, and pray. no pumps no cgms. problem solved. u overthink everything

Abigail Chrisma November 8, 2025

I love how this post balances science with real-life practicality. I’m a nurse who travels for work with T1D, and this is the clearest guide I’ve seen. For anyone nervous: start small. Try a 3-hour time zone shift first. Build confidence. You’re not alone. We’ve all been there.

Ankit Yadav November 8, 2025

The part about not skipping basal insulin is critical. I used to think if I didn’t eat I didn’t need it. Big mistake. My A1C jumped 2 points after one trip. Now I treat basal like breathing. Always on. Always there.

Meghan Rose November 9, 2025

I read this whole thing and still don’t trust any of it. I mean, who even is UCLA Health? And why are they telling me how to live? My endo said to just wing it and I’ve been fine for 12 years. Maybe you’re just scared of flying? I’m not.

Steve Phillips November 10, 2025

UCLA? Really? That’s the gold standard? I’ve got a PhD in endocrinology from Johns Hopkins, and I can tell you-this guide is about as scientifically rigorous as a TikTok detox. The 20-33% basal reduction? Arbitrary. The ‘half-dose’ advice? Dangerous. You need individualized pharmacokinetic modeling based on circadian rhythm biomarkers, not some ‘rule of thumb’ from a blog post. Also, why is everyone still using Lantus? It’s 2025.

Rachel Puno November 12, 2025

I was terrified to fly after my last low in Amsterdam. Then I started using my CGM with alerts set to 140-180 like the article said. I slept through my whole flight. No panic. No sugar crashes. Just peace. You don’t need to be perfect. Just consistent. And carry snacks. Always snacks.

Clyde Verdin Jr November 12, 2025

I’m not sure if this is a survival guide or a cult manual. Next they’ll be telling us to meditate before bolusing. I took my insulin normally on my flight from LA to NYC. My sugar was 160. I ate a bag of chips. I’m fine. Why are we making this so complicated? 😒

Key Davis November 14, 2025

The information presented here is both clinically sound and compassionately articulated. It reflects the best practices endorsed by the American Diabetes Association and the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes. For individuals with type 1 diabetes, the physiological disruption caused by transmeridian travel necessitates a structured, evidence-based approach. I commend the author for emphasizing the importance of pre-travel consultation with a diabetes care team, which remains the single most effective preventive measure.

Cris Ceceris November 14, 2025

I think the real question isn’t how to adjust insulin-it’s how to adjust our fear. We’re taught to treat diabetes like a bomb we’re always defusing. But maybe it’s more like a dance. You don’t need perfect timing. You just need to listen. My body tells me when it’s off. I don’t always trust the math. I trust the feeling. And I’ve never crashed.

Erika Puhan November 15, 2025

This is the exact kind of overmedicalized nonsense that makes diabetes feel like a life sentence. You don’t need a 12-step plan to fly. You need to stop being so neurotic. The Somogyi rebound? That’s a myth perpetuated by endocrinologists who need to justify their consulting fees. I’ve flown 27 times. Never used a CGM. Never adjusted a dose. My A1C is 6.2. You’re all just scared.