RA-Associated PAH Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment Result

Recommendation:

When doctors see a patient with pulmonary arterial hypertension, they often look for underlying causes. One surprising but increasingly recognized trigger is rheumatoid arthritis, a chronic autoimmune disease that attacks joints and, in some cases, the lungs and blood vessels.

Key Takeaways

- PAH occurs in about 1-2% of rheumatoid arthritis patients, but the risk rises with severe joint disease and long‑term inflammation.

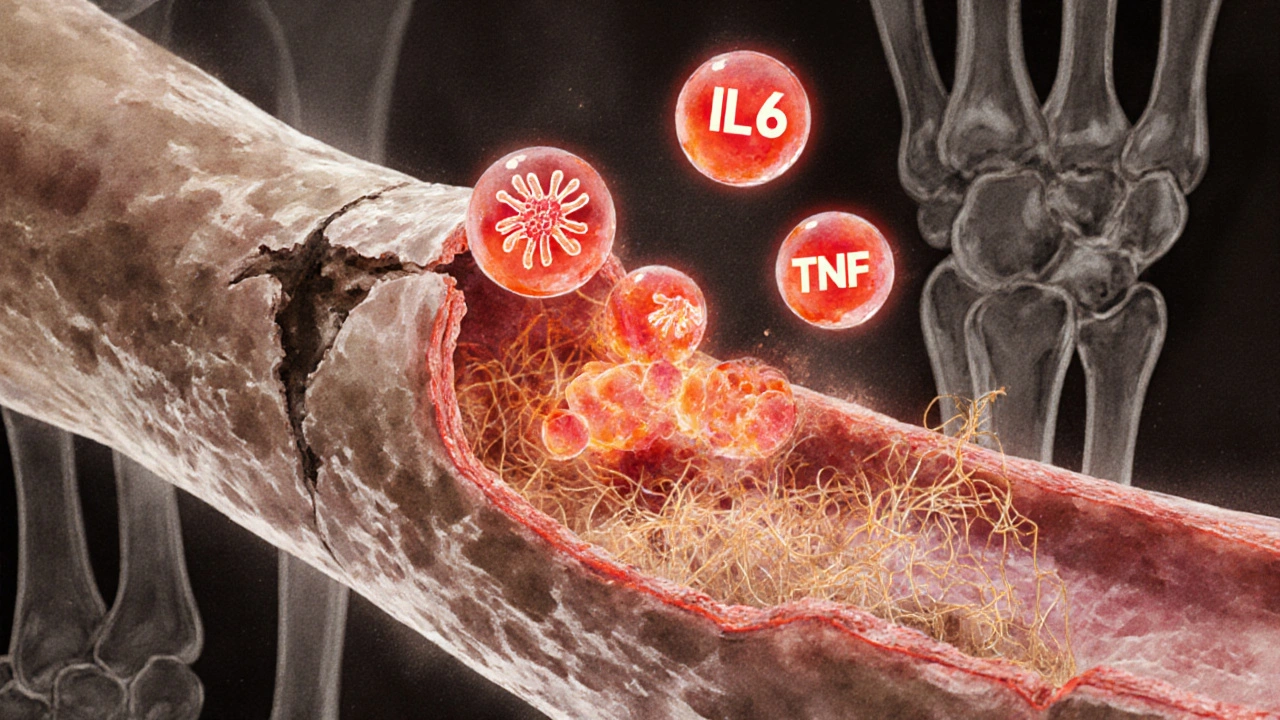

- Shared immune pathways-especially elevated cytokines like IL‑6 and TNF‑α-drive endothelial damage that narrows pulmonary arteries.

- Early screening with echocardiography and right‑heart catheterization can catch PAH before symptoms become disabling.

- Treatment blends PAH‑targeted drugs (e.g., bosentan) with careful management of RA‑related inflammation (e.g., methotrexate, biologics).

- Regular follow‑up of heart function and lung pressure is crucial for long‑term survival.

Below we’ll walk through the epidemiology, the biological bridge between the two diseases, how to spot PAH in a rheumatology clinic, and what treatment looks like when both conditions coexist.

Epidemiology: How Common Is the Overlap?

Large cohort studies from Europe and North America report that roughly 1-2% of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis develop PAH. The prevalence jumps to 5% in patients who also have interstitial lung disease or prolonged high‑dose corticosteroid exposure. Age of onset tends to be later-mid‑50s-compared with idiopathic PAH, which often appears in the 30s‑40s.

Pathophysiology: The Immune Bridge

The link isn’t just a coincidence; it rests on several overlapping mechanisms.

- Autoimmune disease activity fuels chronic systemic inflammation.

- Inflammatory cytokines-particularly interleukin‑6 (IL‑6) and tumor necrosis factor‑alpha (TNF‑α)-circulate at high levels in RA and directly injure the pulmonary arterial endothelium.

- This injury triggers endothelial dysfunction, reducing nitric oxide production and promoting vasoconstriction.

- Endothelial cells begin to proliferate and secrete extracellular matrix, narrowing the vessel lumen-a hallmark of PAH.

- Persistent high pressure forces the right ventricle to work harder, eventually leading to right‑heart failure.

Genetic predisposition also matters. Certain HLA‑DRB1 alleles linked to severe RA have been associated with a higher risk of PAH, suggesting a shared immunogenetic background.

Clinical Presentation: What to Watch For

Patients with PAH and RA often report a blend of joint pain and subtle cardiopulmonary symptoms. Common clues include:

- Unexplained shortness of breath on exertion, especially when joint swelling has already limited activity.

- Fatigue that feels out of proportion to arthritis flare‑ups.

- Chest discomfort or a fainting spell (syncope) during minor physical tasks.

- Peripheral edema-swelling of the ankles-when right‑heart strain sets in.

- Persistent cough or mild haemoptysis, which can be mistaken for medication side effects.

Because these signs overlap with RA‑related lung disease and medication toxicity, a high index of suspicion is essential.

Diagnostic Pathway: From Screening to Confirmation

Guidelines from the 2023 ESC/ERS statement recommend a stepwise approach.

- Screening echocardiogram: Look for an estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure >35mmHg, right‑ventricular enlargement, or interventricular septal flattening.

- If echo is abnormal, proceed to right‑heart catheterization, the gold‑standard test. A mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥20mmHg at rest, with pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ≤15mmHg, confirms PAH.

- Laboratory work‑up should include inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR), autoantibody panels (RF, anti‑CCP), and cytokine levels if available, to gauge the immune burden.

- High‑resolution CT of the chest helps rule out interstitial lung disease, which would shift management toward WHO Group3 rather than Group1 PAH.

Early detection improves outcomes dramatically: survival at five years can rise from 50% to over 70% when therapy starts within six months of diagnosis.

Management Strategies: Treating Both Sides of the Coin

Therapy must address two fronts-pulmonary pressures and systemic inflammation-while avoiding drug interactions.

PAH‑Targeted Medications

First‑line agents include endothelin‑receptor antagonists (ERAs) such as bosentan, phosphodiesterase‑5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil), and prostacyclin analogues (iloprost, selexipag). In RA patients, bosentan is often preferred because it doesn’t exacerbate liver enzymes as strongly as some other ERAs, though liver function still needs routine monitoring.

Controlling Rheumatoid Inflammation

Traditional disease‑modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) like methotrexate remain first‑line for joint disease. However, methotrexate can cause pulmonary toxicity, so clinicians may choose leflunomide or biologics (e.g., tocilizumab, an IL‑6 blocker) when PAH risk is high.

Biologics that target IL‑6 or TNF‑α have a dual benefit: they suppress joint inflammation and may blunt the cytokine‑driven endothelial damage that fuels PAH. Small trials with tocilizumab showed modest reductions in pulmonary artery pressure in RA‑associated PAH, though larger studies are pending.

Combination Approach and Monitoring

Most experts recommend a ‘treat‑to‑target’ model: titrate PAH drugs to achieve a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure <25mmHg and a six‑minute walk distance >380m. Simultaneously, aim for a DAS28 (Disease Activity Score) <2.6 to keep RA quiescent.

Regular follow‑up every three months includes echo, NT‑proBNP levels, and joint assessments. Any rise in liver enzymes, creatinine, or worsening dyspnea prompts medication review.

Prognosis and Long‑Term Outlook

Historically, PAH linked to autoimmune disorders carried a poorer prognosis than idiopathic PAH, mainly because of delayed diagnosis and overlapping drug toxicities. With today’s screening protocols and combined therapy, median survival now exceeds eight years, approaching rates seen in isolated PAH.

Key predictors of better outcomes are:

- Early detection (within six months of symptom onset)

- Controlled RA disease activity (low CRP, low DAS28)

- Absence of significant interstitial lung disease

- Responsive hemodynamics to initial PAH therapy

Patients who maintain these targets often report a quality‑of‑life comparable to those with only RA.

Practical Checklist for Clinicians

| Marker | Typical Value in PAH‑RA | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure | ≥20mmHg (right‑heart cath) | Start ERA or PDE‑5 inhibitor |

| NT‑proBNP | Elevated >300pg/mL | Monitor cardiac strain |

| IL‑6 level | Often >10pg/mL | Consider IL‑6 blocker (tocilizumab) |

| CRP/ESR | High during RA flares | Intensify DMARD/biologic therapy |

| DLCO (diffusing capacity) | Reduced <70% predicted | Rule out interstitial lung disease |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can rheumatoid arthritis cause pulmonary arterial hypertension on its own?

Yes. Chronic systemic inflammation in RA can damage the pulmonary vessels, especially when the disease is uncontrolled or when patients have additional lung involvement.

Should every RA patient be screened for PAH?

Screening is recommended for RA patients who have symptoms like unexplained dyspnea, those on long‑term high‑dose steroids, or those with co‑existing interstitial lung disease. An annual echocardiogram is a reasonable baseline.

Do PAH medications interact with common RA drugs?

Some ERA drugs can raise liver enzymes, which may be problematic if methotrexate is also used. Regular liver function tests and dose adjustments usually keep both therapies safe.

Is there a role for biologic therapy in treating PAH itself?

Biologics that block IL‑6 or TNF‑α have shown promise in reducing pulmonary artery pressure in small studies, but they are not yet first‑line PAH drugs. They are used primarily to control RA inflammation, which indirectly benefits PAH.

What is the long‑term outlook for patients with both conditions?

If PAH is caught early and RA is well‑controlled, many patients live a near‑normal life for 8‑10years after diagnosis. Ongoing monitoring and a combined treatment strategy are key to that outcome.

12 Comments

Yareli Gonzalez October 9, 2025

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a serious complication that can catch many RA patients off guard. Early screening tools, like the risk calculator shown here, can help clinicians spot subtle warning signs. Incorporating routine echocardiography into the annual RA assessment could save lives. Also, keeping steroid doses as low as possible may reduce vascular stress. Remember, patient education is key to early detection.

Alisa Hayes October 11, 2025

Your summary of the risk factors hits the nail on the head, especially regarding disease duration and corticosteroid exposure. It’s worth noting that interstitial lung disease adds an extra layer of hemodynamic burden, often overlooked in routine visits. Autoantibody positivity, particularly RF and anti‑CCP, correlates with more aggressive vascular inflammation. Age above fifty contributes to endothelial dysfunction, compounding the PAH risk. Clinicians should balance immunosuppression with cardiovascular monitoring to avoid iatrogenic harm. A multidisciplinary approach, involving rheumatology and pulmonology, makes the most sense.

Mariana L Figueroa October 13, 2025

Managing RA aggressively can blunt the inflammatory cascade that drives pulmonary hypertension. Keep up the regular follow‑ups and watch those lung function numbers.

mausumi priyadarshini October 14, 2025

Interestingly, the supposed link between RA and PAH is often overstated, isn’t it? Many studies cite correlation, yet causation remains elusive; the data are mixed. One could argue that steroids, rather than the arthritis itself, muddy the waters, complicating the risk assessment. Moreover, the calculator ignores genetic predispositions, which some researchers deem critical, leading to potential misclassification. So perhaps we should treat this tool with a healthy dose of skepticism!

Carl Mitchel October 16, 2025

Let’s be clear: allowing PAH to develop in RA patients reflects a systemic failure in preventive care. The medical community has been aware of the vascular implications for decades, yet many clinics still neglect routine right‑heart evaluation. It is irresponsible to rely solely on symptom reporting, because dyspnea is often attributed to joint pain. Proactive echocardiograms should be ordered whenever steroid doses exceed low‑grade thresholds. Ignoring the autoantibody profile is equally negligent, given its prognostic value. We owe patients a comprehensive screening regimen, not a half‑hearted checklist.

Suzette Muller October 18, 2025

I’ve seen several patients benefit from early PAH detection through regular screening. Integrating the risk calculator into your clinic workflow can flag high‑risk individuals before symptoms appear. Collaborating with a cardiologist experienced in pulmonary hypertension ensures appropriate follow‑up. Remember, a supportive environment encourages patients to share subtle respiratory changes.

Taryn Bader October 20, 2025

Wow, this calculator looks like a crystal ball for doctors!

Myra Aguirre October 21, 2025

Looks useful, especially for busy clinics. I think the easy drop‑downs make it user‑friendly. Hope it helps catch those silent cases early.

Shawn Towner October 23, 2025

While the enthusiasm surrounding the RA‑PAH risk calculator is palpable, a more measured perspective is warranted. The pathophysiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension in rheumatoid arthritis is multifactorial, extending beyond the simplistic variables listed. Chronic systemic inflammation, mediated by cytokines such as IL‑6 and TNF‑α, contributes to endothelial dysfunction, yet this is not captured by the current model. Furthermore, the role of genetic polymorphisms, particularly those affecting BMPR2 signaling, remains largely unaddressed. This omission is significant because hereditary factors can predispose patients to PAH irrespective of rheumatologic disease activity. Age, while included, is treated as a binary threshold, ignoring the nuanced decline in vascular compliance that occurs across the lifespan. The duration of disease is factored in a linear fashion, but flares and remission periods can dramatically alter the inflammatory burden. Corticosteroid dosing is another crude proxy; the impact of biologic agents, such as abatacept or tocilizumab, on pulmonary pressures is not reflected. Interstitial lung disease, a common comorbidity in RA, is reduced to a simple yes/no, disregarding the spectrum of radiographic patterns that differentially affect hemodynamics. Autoantibody status is listed, yet the quantitative titer and affinity of antibodies can influence vascular immune complexes, a detail the calculator omits. From a clinical workflow standpoint, the tool’s reliance on self‑reported data may introduce bias, especially in patients with limited health literacy. Moreover, the absence of a validation cohort from diverse ethnic backgrounds raises concerns about its universal applicability. In practice, overreliance on such a calculator could lead to a false sense of security, delaying more definitive investigations like right heart catheterization. Conversely, it may also generate unnecessary anxiety for low‑risk patients who are flagged erroneously. A more robust algorithm would incorporate biomarkers such as NT‑proBNP, pulmonary function trends, and perhaps even machine‑learning derived risk scores. Until such refinements are made, clinicians should treat this calculator as an adjunct, not a definitive decision‑making tool. In summary, the concept is laudable, but premature adoption without rigorous validation risks compromising patient care. Proceed with caution, and always corroborate calculator outputs with comprehensive clinical assessment.

Capt Jack Sparrow October 25, 2025

Yeah, the calculator’s got some solid points, but don’t let it be the only thing you trust. I’ve seen cases where the score was low yet the echo showed early right‑ventricular strain. It’s a good conversation starter with patients, though. Just remember to order a baseline six‑minute walk test and BNP level for a fuller picture. Bottom line: use it, but keep your own clinical instincts sharp.

Manju priya October 27, 2025

Congratulations on taking the initiative to assess PAH risk in rheumatoid arthritis patients! 😊 Implementing this calculator can empower both clinicians and patients to engage in proactive health management. I encourage you to pair the results with regular cardiopulmonary evaluations for optimal outcomes. Let’s continue driving forward with evidence‑based strategies and collaborative care.

Jesse Groenendaal October 28, 2025

We cannot ignore the ethical duty to screen for PAH in high‑risk RA groups. Failure to do so is simply unacceptable.