Syphilis Treatment Calculator

Select Syphilis Stage

Recommended Treatment

Penicillin is the gold standard treatment

For penicillin-allergic patients:

Follow-up required:

Key Takeaways

- Syphilis moves through four main stages, each with distinct signs and risks.

- Early detection relies on simple blood tests and careful symptom checks.

- Penicillin remains the gold‑standard treatment for all stages.

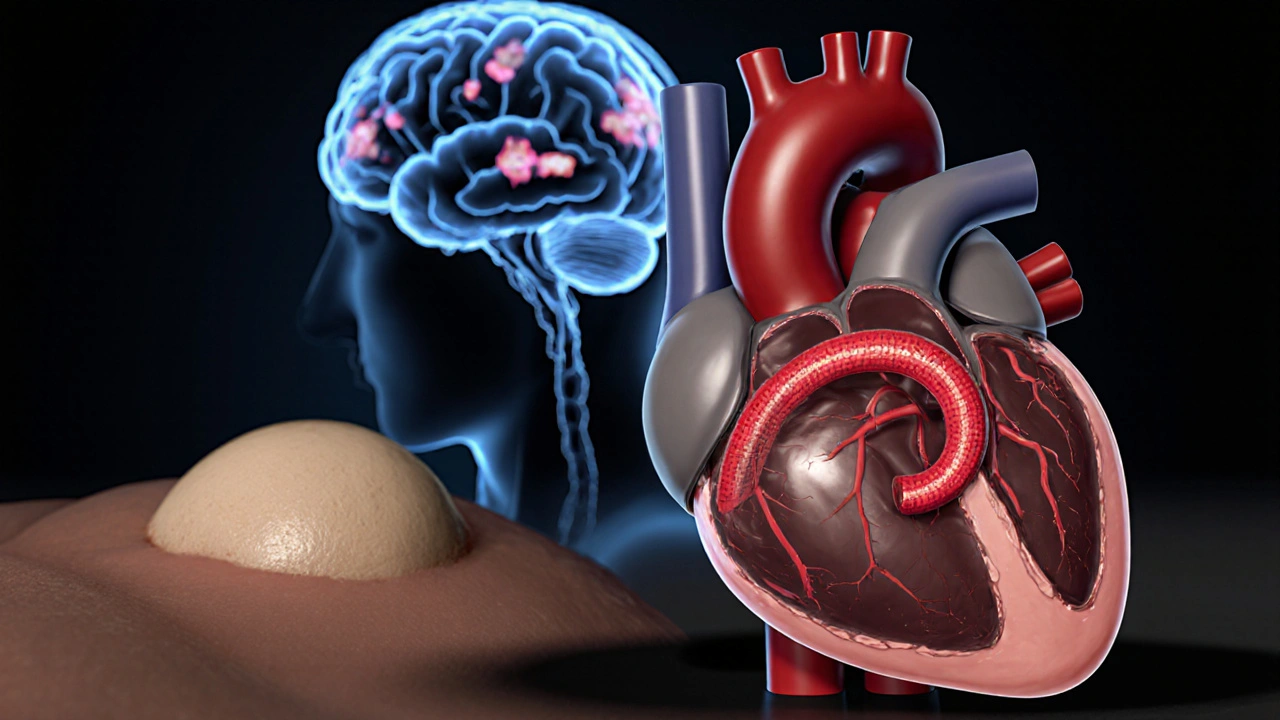

- Untreated infection can damage the heart, brain, and even unborn babies.

- Prevention and prompt medical care stop the disease before it spreads.

When you hear the word Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, you might picture a single illness with one set of symptoms. In reality, the infection unfolds in a series of stages, each with its own timeline, clinical picture, and treatment nuances. Understanding the syphilis stages helps you recognize warning signs early, get the right tests, and start the effective therapy that prevents long‑term damage.

What Is Syphilis?

Syphilis is a bacterial infection transmitted primarily through sexual contact, but it can also pass from a pregnant person to their baby. The culprit, Treponema pallidum is a spiral‑shaped spirochete that can invade skin, mucous membranes, and internal organs.

Because the bacterium spreads silently for weeks or months, many people never realize they’re infected until later complications appear. That’s why a clear picture of each disease phase is critical for timely care.

How the Disease Progresses

Syphilis traditionally follows a predictable pattern, though the timing can vary. After exposure, the bacterium multiplies locally, then travels through the bloodstream, setting the stage for the next phase. Below is a quick timeline:

- 0-4 weeks: Primary stage (chancre appears)

- 4-12 weeks: Secondary stage (rash, systemic symptoms)

- 3 months to several years: Latent stage (no symptoms, but infection persists)

- 5-15 years (or later): Tertiary stage (organ damage, neurosyphilis, cardiovascular issues)

Not everyone reaches the tertiary stage-effective treatment at any earlier point halts progression.

Primary Stage

Primary syphilis is a stage marked by a painless ulcer called a chancre that appears at the site where the bacteria entered the body-usually the genitals, anus, or mouth. The sore is firm, round, and may go unnoticed because it hurts little and often heals on its own within 3-6 weeks.

Key symptoms include:

- Single or multiple chancres

- Swollen, non‑tender lymph nodes nearby

Because the chancre can disappear without treatment, a blood test is the only reliable way to confirm infection. The standard screening uses non‑treponemal tests like RPR (Rapid Plasma Reagin) or VDRL, followed by a treponemal confirmatory test such as FTA‑ABS.

Treatment for primary syphilis is a single intramuscular dose of Penicillin is the first‑line antibiotic that eradicates Treponema pallidum. Alternatives like doxycycline exist for penicillin‑allergic patients, but they require a longer course.

Secondary Stage

Secondary syphilis is a phase characterized by widespread skin rashes, mucous‑membrane lesions, and systemic symptoms. It typically emerges 4-10 weeks after the chancre and can last several weeks to months.

Common signs include:

- Reddish‑brown rash on palms, soles, trunk, or limbs (often described as “nickel‑coin” lesions)

- Moist, raised lesions called condylomata lata in the genital area

- Fever, sore throat, headache, muscle aches

- Patchy hair loss (especially on the scalp)

Because the rash can mimic other conditions, a doctor will order the same serologic panel used in the primary stage. Repeat testing may show higher antibody titers.

Penicillin therapy remains the same-usually one dose for early disease-but some clinicians add a second dose if symptoms linger.

Latent Stage

After the secondary rash fades, the infection enters the latent stage is a period without visible symptoms, but the bacteria stay alive in the body. This stage splits into two sub‑phases:

- Early latent - within the first year after infection. Patients are still contagious, and regular blood tests will show active titers.

- Late latent - beyond one year. Infectiousness drops, but the risk of progressing to tertiary disease rises.

Because you feel fine, many people skip follow‑up appointments. Health guidelines recommend at least three serologic tests over two years for anyone diagnosed with earlier stages.

Even in the latent stage, the recommended treatment is a full 2‑week course of Penicillin, administered as 2.4 million units intramuscularly each day for three consecutive days (the “Benzathine penicillin G” regimen).

Tertiary Stage

If infection remains untreated for years, it can advance to tertiary syphilis is a late stage that damages internal organs, especially the heart, blood vessels, and nervous system. Only about 15-30% of untreated cases reach this point, but the consequences are severe.

Major manifestations include:

- Gummatous lesions - soft, tumor‑like growths that can appear on skin, bone, or liver.

- Cardiovascular syphilis - aneurysms of the aorta, aortic valve insufficiency, and coronary artery disease.

- Neurosyphilis - infection of the central nervous system, causing headaches, personality changes, numbness, or even paralysis.

Neurosyphilis can emerge at any stage, but it’s most common in the tertiary phase. Diagnosis requires lumbar puncture and specific cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests (VDRL on CSF). If positive, the treatment escalates to intravenous penicillin for 10-14 days.

Standard benzathine penicillin may still be used for non‑neurologic tertiary disease, but many clinicians opt for the same intensive IV regimen to ensure CSF penetration.

Congenital Syphilis

When a pregnant person is infected, congenital syphilis is a serious condition passed to the baby during pregnancy or delivery. Babies can be born with rash, bone abnormalities, organ failure, or may die shortly after birth.

The CDC recommends universal screening at the first prenatal visit and again in the third trimester for high‑risk women. Early maternal treatment with penicillin prevents almost all cases.

Diagnosis Across All Stages

Because the symptoms shift, clinicians rely heavily on serologic testing:

- Non‑treponemal tests (RPR, VDRL) - detect antibodies produced in response to cellular damage; useful for monitoring treatment response.

- Treponemal tests (FTA‑ABS, TP‑PA) - detect antibodies specific to Treponema pallidum; remain positive for life.

For neurosyphilis, a spinal tap adds CSF VDRL and cell count. Dark‑field microscopy can directly visualize spirochetes from chancre fluid, but it’s rarely available outside specialist centers.

Treatment Overview

Penicillin remains the cornerstone of therapy because it reaches high concentrations in blood, CSF, and tissues. Regimens differ by stage:

| Stage | Typical Duration | Key Symptoms | Treatment Regimen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | 1-4 weeks | Single painless chancre, regional lymphadenopathy | Single 2.4MU IM dose of Benzathine penicillin G |

| Secondary | Weeks to months | Palm‑sole rash, mucous‑membrane lesions, fever, malaise | Same single dose as primary (or repeat if needed) |

| Latent (early) | Up to 1year | No visible signs; serology positive | Three weekly 2.4MU IM doses |

| Latent (late) | >1year | No visible signs; higher risk of complications | Same three‑dose regimen; consider CSF exam |

| Tertiary (incl. neurosyphilis) | Years after infection | Gummas, aortic aneurysm, neurologic deficits | IV Penicillin G 18-24MU/day for 10-14days |

For patients allergic to penicillin, desensitization is preferred over alternative antibiotics because cross‑reactivity with other classes is a concern.

Prevention & When to Seek Care

Safe sexual practices-condom use, limiting partners, and regular STI screening-stop syphilis before it starts. If you notice any of the hallmark signs (a chancre, unusual rash, swollen lymph nodes), schedule a doctor’s visit right away. Early treatment not only cures you but also protects anyone you may have exposed.

Pregnant individuals should get screened at the first prenatal appointment. If a test is positive, immediate penicillin therapy dramatically reduces the risk of congenital infection.

Patient Checklist

- Know your risk factors: unprotected sex, multiple partners, previous STIs.

- Watch for early signs: painless sore, rash on palms/soles, flu‑like symptoms.

- Get tested: request RPR/VDRL and confirm with FTA‑ABS.

- Follow treatment exactly: complete the full penicillin course.

- Return for follow‑up serology at 3, 6, and 12months to ensure antibody titers drop.

- Inform recent partners so they can be tested and treated.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can syphilis go away on its own without treatment?

No. The bacteria remain in the body and will eventually progress to later stages if left untreated. Even if symptoms disappear, the infection is still active.

Is a painless sore always a syphilis chancre?

Not always. Other conditions like herpes or a simple irritation can look similar. A blood test confirms whether the sore is caused by syphilis.

How soon after exposure can I test positive?

Non‑treponemal tests usually become positive 1-3 weeks after infection. If you test too early, repeat after a week.

Can I use antibiotics at home instead of seeing a doctor?

Self‑treating is risky. Proper dosing, especially for later stages, requires a healthcare professional’s supervision and follow‑up blood work.

What are the chances of passing syphilis to a baby?

Without treatment, transmission rates are as high as 60-80%. Early penicillin treatment reduces that risk to less than 2%.

17 Comments

Alex EL Shaar October 12, 2025

Alright, let’s dissect this syphilis deep‑dive the way a toxic analyst would love to tear apart every bullet point. First off, the article’s opening line tries to sound all scientific but drops the ball with a sloppy “caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum” – no italics, no proper genus‑species formatting, cringe. Then it jumps straight into a JavaScript snippet that looks like it was copy‑pasted from a web dev forum, completely irrelevant to a medical article – talk about misplaced focus. The stage breakdown is decent, but the list of symptoms is peppered with redundant phrasing like “painless sore” and “painless ulcer” – why not just pick one term and stick with it? The treatment section correctly emphasizes penicillin, yet it neglects to mention that doxycycline is not just a fallback; it’s the recommended alternative for pregnant patients allergic to penicillin, which is a massive omission. Also, the article says “early detection relies on simple blood tests,” but fails to note the window period for seroconversion – readers might get a false sense of security testing too early. The latency explanation mixes up “early latent” and “late latent” with vague timelines – clearer cutoffs (within one year vs. beyond one year) would save confusion. The table at the end is a nice touch, but the HTML is a mess, missing proper tags and the rows are not aligned, making it hard to read on mobile. The “Key Takeaways” bullet points are a good summary, though the fourth point about “untreated infection can damage the heart, brain, and even unborn babies” could be expanded with stats to drive the point home. There’s also an awkward line break before “When you hear the word Syphilis…” that looks like a leftover from a template. The FAQs are useful, but the answer to “Can syphilis go away on its own?” is too brief – a quick note about the chronic nature of the disease would be better. Finally, the article could benefit from a brief mention of the rise in syphilis rates in the past decade, linking to CDC data for readers who want to see the epidemiological trend. Overall, the content is solid, but the execution suffers from editorial sloppiness, missed nuances, and a few downright careless copy‑pastes.

-

Health and Wellness

-

Pharmacy

-

Medicines

-

Health and Medicine

-

Nutrition and Supplements

-

Men's Health

-

Healthcare

-

Women's Health

-

Skincare and Beauty

-

Fitness

-

dietary supplement

-

medication safety

-

side effects

-

health benefits

-

online pharmacy

-

generic drugs

-

drug interactions

-

alternatives

-

bioequivalence

-

mental health

-

blood pressure medication

-

Viagra alternatives

-

online pharmacy safety

-

medication errors

-

precautions

-

osteoporosis

-

hiv treatment

-

connection

-

athletes

-

Stromectol

Anna Frerker October 13, 2025

This reads like a textbook written by a bored intern.

Alexandre Baril October 14, 2025

Hey folks, if you’re looking for a quick rundown, the key is to remember that each stage builds on the previous one and the treatment gets more aggressive as you move forward. Primary syphilis is handled with a single penicillin shot, secondary is the same, but latent stages require multiple doses, and tertiary needs IV penicillin. Also, always follow up with serology at 3, 6, and 12 months to make sure the infection is cleared. Keep an eye on any new symptoms, especially neurological signs, and get tested if you think you’ve been exposed.

Stephen Davis October 15, 2025

Exactly, Alex! Adding to that, it helps to have a small checklist on hand – know your risk factors, watch for the chancre or rash, and schedule those follow‑up labs. It’s easy to forget the timeline, but the 1‑year cutoff between early and late latent is crucial for deciding the dosing schedule.

Grant Wesgate October 16, 2025

Good summary, everyone! 😊 Just a reminder to always tell recent partners to get tested – it saves a lot of headache down the line.

benjamin malizu October 17, 2025

While the above points are practically sound, the moral imperative cannot be ignored: failing to comply with treatment protocols is not just a personal health issue but a public health betrayal. Ignorance or laziness in seeking treatment propagates the infection, undermining community health initiatives. The legal ramifications of knowingly transmitting a curable STI can be severe, and the ethical duty to protect others should supersede any personal inconvenience. Therefore, adherence to the recommended penicillin regimen and rigorous follow‑up is not optional – it is an ethical responsibility.

Maureen Hoffmann October 18, 2025

I love how this post breaks everything down into bite‑size pieces. For anyone feeling overwhelmed, just start with the primary stage checklist and work your way up. Remember, you’re not alone – many people have gone through this and come out fine with proper care.

Alexi Welsch October 19, 2025

It is incumbent upon the author to remark upon the glaring omission of recent epidemiological data, which, in a scholarly treatise, constitutes a substantive deficiency. The lack of citation of CDC surveillance statistics diminishes the work’s authority.

Louie Lewis October 20, 2025

Ever notice how every article about STIs conveniently leaves out the fact that pharmaceutical companies push penicillin to keep their profit margins high? The whole “gold standard” narrative feels orchestrated.

Eric Larson October 21, 2025

Wow!!! That’s a bold claim!!! But where’s the evidence???!!! If you’re going to throw around conspiracy jargon, at least back it up with credible sources!!!

Kerri Burden October 22, 2025

Just a heads‑up: the article could add a note about the importance of testing during the window period – early tests can be false‑negative.

Joanne Clark October 23, 2025

Interesting read, though the formatting could be improved, especially the table.

Sriram Musk October 24, 2025

The information is solid, but adding a quick visual flowchart would help learners retain the stage progression.

allison hill October 25, 2025

While the article is thorough, one must question the source of the treatment guidelines – are they truly up‑to‑date?

Tushar Agarwal October 25, 2025

Great post! 👍 If anyone needs a quick reminder, just remember: penicillin works, follow‑ups matter, and don’t forget to tell your partners.

Richard Leonhardt October 26, 2025

Absolutely! Keeping the community informed is key. If you’re ever unsure, a quick call to your local health department can clear things up fast.

Ariel Munoz October 27, 2025

Let’s be clear: this is a battle of public health versus complacency. We can’t afford half‑measures – full compliance with penicillin protocols is non‑negotiable for the safety of our nation.

Write a comment

Categories

Recent Posts

Where and How to Safely Buy Suprax Online: Tips and Guide

When Doctors Say 'Do Not Substitute': Why Brand-Name Drugs Are Sometimes Necessary

Using Two Patient Identifiers in the Pharmacy for Safety: How It Prevents Medication Errors

How Drug-Drug Interactions Work: Mechanisms and Effects Explained

Verifying Your Prescription at the Pharmacy: A Simple Patient Checklist to Avoid Medication Errors

Tags