Chronic Hepatitis C is a long‑term infection caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that gradually damages liver tissue and can lead to cirrhosis or cancer. While many people carry the virus without feeling sick, the hidden damage builds up over years. This guide walks you through why the virus sticks around, what clues it gives you, and which medicines now offer a cure in most cases.

Key Takeaways

- HCV spreads mainly through blood exposure; needle sharing tops the risk list.

- Symptoms often hide for decades; routine screening is the only reliable detection method.

- Direct‑acting antivirals (DAAs) achieve cure rates above 95% with few side effects.

- Successful treatment is measured by a sustained virologic response (SVR) 12 weeks after therapy.

- Lifestyle steps-vaccination, alcohol moderation, and regular liver checks-help preserve liver health after cure.

Understanding the Virus

Hepatitis C virus is a single‑stranded RNA virus (family Flaviviridae) that infects liver cells and hijacks their machinery to replicate. HCV exists in seven major genotypes (1‑7) and dozens of sub‑types, each differing slightly in genetic sequence. Genotype influences treatment length and drug selection, but modern DAAs cover all genotypes in a single pill regimen.

The virus enters the bloodstream via direct contact with infected blood. Once inside, it silently replicates, triggering chronic inflammation that scars liver tissue (fibrosis) over time.

Who’s at Risk?

Risk groups share a common thread: exposure to contaminated blood.

- People who inject drugs (PWID) - the single largest driver of new infections.

- Recipients of unscreened blood transfusions before 1992.

- Healthcare workers with needlestick injuries.

- Those undergoing hemodialysis without strict infection control.

- Individuals born between 1945‑1965, a demographic with higher historic exposure.

Genotype distribution also varies geographically. In the United States, genotype1 accounts for about 70% of cases, while genotype3 is more common in South Asia.

Symptoms - The Silent Progression

Most people feel fine for years. When symptoms emerge, they often mimic other illnesses:

- Persistent fatigue or low‑grade fever.

- Dark urine and pale stool.

- Joint or muscle aches.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Abdominal discomfort, especially in the right upper quadrant.

Because these signs are vague, many patients discover HCV during routine blood work, not because they felt sick.

How Doctors Diagnose Chronic Hepatitis C

The diagnostic algorithm blends serology and molecular testing:

- Anti‑HCV antibody test - detects prior exposure; a positive result triggers confirmatory testing.

- HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) - measures viral load and confirms active infection.

- Genotype assay - identifies the specific viral genotype to guide therapy.

- Liver function panel - ALT, AST, bilirubin, and albumin levels reveal liver inflammation.

- Fibrosis assessment - non‑invasive elastography (FibroScan) or serum‑based scores (APRI, FIB‑4) estimate scar tissue.

When advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis is suspected, imaging (ultrasound, CT, MRI) and sometimes a liver biopsy are added for precision.

Treatment Landscape

Therapy has shifted dramatically in the past decade.

Older Regimens: Interferon‑Based Therapy

Before 2014, treatment relied on pegylated interferon‑α combined with ribavirin. Cure rates hovered around 50% for genotype1 and 70‑80% for easier genotypes, but patients endured flu‑like symptoms, depression, and anemia.

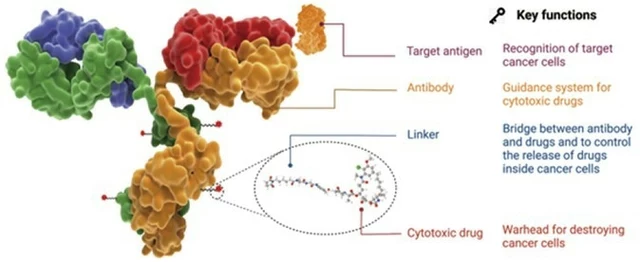

Modern Era: Direct‑Acting Antivirals (DAAs)

Direct‑acting antivirals are a class of oral medications that target specific HCV proteins (NS5A, NS5B, NS3/4A) and block viral replication. By interrupting the virus’s life cycle, DAAs clear the infection in most people within 8‑12 weeks.

Key advantages include:

- >95% sustained virologic response (SVR) across genotypes.

- Minimal side effects-often just mild fatigue or headache.

- No injections, no interferon‑related depression.

- Shorter treatment courses (8‑12 weeks for most patients).

Comparing Popular DAA Regimens

| Regimen | Duration | Cure Rate (SVR12) | Genotype Coverage | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir | 12 weeks (8 weeks for non‑cirrhotic genotype1‑3) | ≈98% | All genotypes (1‑6) | Headache, fatigue |

| Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir | 8 weeks (extended to 12 weeks for cirrhosis) | ≈97% | All genotypes (1‑6) | Diarrhea, mild nausea |

| Elbasvir/Grazoprevir | 12 weeks | ≈95% | Genotype1, 4, 5, 6 | Fatigue, headache |

Choosing a regimen depends on genotype, presence of cirrhosis, kidney function, and potential drug-drug interactions. Your provider will match the best option to your health profile.

Sustained Virologic Response (SVR)

The gold standard for cure is an sustained virologic response defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level 12 weeks after completing therapy. Achieving SVR dramatically lowers the risk of liver cancer and extends life expectancy to near‑normal levels.

Living After Cure

Even after viral clearance, the liver may retain scar tissue. Ongoing care includes:

- Annual ultrasound screening for hepatocellular carcinoma if pre‑treatment fibrosis was advanced.

- Vaccination against hepatitis A and B (no vaccine exists for HCV).

- Limiting alcohol intake to protect remaining healthy liver cells.

- Maintaining a balanced diet rich in antioxidants-fruits, vegetables, lean protein.

- Regular follow‑up labs (ALT, AST) to monitor liver function.

People who achieve SVR also benefit from reduced cardiovascular risk and improved insulin sensitivity, underscoring the systemic payoff of cure.

Related Topics to Explore

If you’re curious how hepatitis C fits into the bigger picture of liver health, consider reading about:

- Hepatitis B infection - another viral liver disease with an effective vaccine.

- Liver cirrhosis - the end‑stage scarring process common to many chronic liver injuries.

- Alcohol‑related liver disease - a major co‑factor that accelerates HCV progression.

- Non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) - a growing cause of liver inflammation worldwide.

- HIV/HCV co‑infection - treatment nuances when both viruses are present.

Understanding these connections helps you keep your liver in top shape, whether or not you ever contract HCV.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can chronic hepatitis C be asymptomatic?

Yes. Up to 70% of people with chronic infection never notice symptoms until liver damage is advanced. That’s why routine screening for at‑risk groups is essential.

How long does it take to cure hepatitis C with DAAs?

Most DAA regimens are taken for 8‑12 weeks. An SVR12 test, performed 12 weeks after the last dose, confirms cure.

Is there any vaccine for hepatitis C?

No. Unlike hepatitis A and B, no vaccine exists for HCV because the virus mutates rapidly, making a stable target hard to develop.

Can I drink alcohol while on treatment?

Alcohol is not a direct interaction with DAAs, but it stresses the liver. Doctors usually advise limiting or avoiding alcohol during therapy and afterward.

What happens if the virus returns after cure?

Re‑infection is possible, especially if risk behaviors continue. However, a cured liver is healthier and more resilient, so routine monitoring remains important.

16 Comments

harvey karlin September 24, 2025

DAAs are a godsend. We went from ‘interferon hell’ to ‘take a pill, go to the gym, live your life.’ No more weekly shots, no more depression spirals. It’s like swapping a typewriter for a quantum computer. The virus didn’t stand a chance.

Anil Bhadshah September 26, 2025

Just wanted to add - if you're in India and got tested via private lab, make sure they use real-time PCR, not just antibody. Saw too many false negatives because of cheap kits. Also, generic sofosbuvir/velpatasvir is now under $100 a course. Life-changing.

lili riduan September 27, 2025

I cried when my doctor said ‘SVR12’ - not because I was sick, but because I finally felt like I could breathe again. I was 32 and felt 70. Now I’m hiking, cooking, dancing. This isn’t just medicine. It’s a second chance.

Trupti B September 29, 2025

so i got hep c from a tattoo in 2010 and never told anyone cause i was scared but now im cured and its like a weight lifted off my chest lol

VEER Design September 30, 2025

They say HCV is silent, but it screams in your liver’s silence. We treat the virus like a ghost - invisible until it collapses the house. DAAs don’t just kill the virus, they restore dignity. The real miracle isn’t the drug - it’s that we finally stopped blaming the patient.

Leslie Ezelle October 1, 2025

Let’s be real - the pharma companies didn’t make these drugs out of kindness. They saw a $100B market and finally had the tech to monetize it. Now they’re hiking prices again. Don’t let the ‘95% cure rate’ distract you from the greed behind it.

Dilip p October 2, 2025

One thing people overlook: curing HCV doesn’t undo decades of stigma. I got tested after my cousin passed from liver cancer. I was terrified of being labeled a ‘junkie’ - even though I got it from a blood transfusion in ’89. The cure healed my liver, but not the shame.

Kathleen Root-Bunten October 2, 2025

Is there any data on how many people with SVR still develop liver cancer? I read somewhere that fibrosis doesn’t fully reverse - even if the virus is gone. Should we be doing annual biopsies? Or is FibroScan enough? Just curious.

Vivian Chan October 3, 2025

Did you know the CDC quietly stopped tracking HCV in 2018 because the numbers dropped too fast? They didn’t want to admit how many people were cured - it made the needle-sharing crisis look less urgent. Now funding’s drying up. This isn’t science. It’s politics.

andrew garcia October 5, 2025

It’s funny - we cured HCV with pills, but we still can’t cure the stigma. People think if you had it, you must’ve done something wrong. But the virus doesn’t care if you’re a nurse, a veteran, or a grandparent who got a transfusion in 1975. It’s not a moral failure. It’s biology.

ANTHONY MOORE October 6, 2025

My uncle got treated last year. He’s 68, never used drugs, never even drank. Got it from a surgery in the 80s. Now he’s back to gardening, playing with his grandkids. Just goes to show - you don’t have to be ‘high risk’ to be infected. Everyone should get tested once.

Jason Kondrath October 8, 2025

Look, the article reads like a pharmaceutical brochure. ‘95% cure rate!’ Sure. But what about the 5% who fail? What about the liver cancer that still develops post-SVR? And why is genotype 3 still harder to treat? This is cherry-picked optimism wrapped in a glossy PDF.

Jose Lamont October 8, 2025

There’s something beautiful about how science quietly fixed this. No fanfare. No viral TikToks. Just doctors, labs, and pills. We didn’t need heroes - we needed patience. And now, for the first time in decades, we’re giving people back their future, one 8-week course at a time.

Ruth Gopen October 9, 2025

I’m a nurse in a rural ER. Last month, a 24-year-old came in with jaundice. Said he got it from sharing straws at a party. I told him about DAAs. He cried. Said he thought he was going to die. We got him on treatment within 72 hours. That’s the real win - not the cure rate. It’s the moment someone believes they deserve to live.

Tejas Manohar October 11, 2025

While the efficacy of direct-acting antivirals is indisputable, it is imperative to underscore that access remains inequitable. In low-resource settings, cost barriers, regulatory delays, and fragmented healthcare infrastructure prevent even the most curative regimens from reaching those who need them most. A 95% cure rate is meaningless if 80% of the global burden remains untreated. This is not merely a medical challenge - it is a moral one.

Mohd Haroon October 13, 2025

One must contemplate the metaphysical paradox: we have eradicated the virus from the bloodstream, yet society persists in branding the cured as ‘contaminated.’ The body is healed, but the soul remains scarred by the stigma of association. Is cure not liberation? Or merely a transition from one prison to another - from biological captivity to social exile?